I came across this article in the LA Times about ship-breaking in Bangladesh.

http://www.latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-bangladesh-ships-20160309-story.html

Anth256 Space, Place and Infrastructure

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

Smelling Life in Capitalist Ruins

Anna Tsing's The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins reads like a science fiction novel. Perhaps that's partly the reason why books that engage seriously with the divides between humans and nonhumans (e.g. the growing scholarship on aspects of post humanism) draw heavily from literary sources like Tsing's reviewer Ursula K. Le Guin or others like Octavia Butler who have fundamentally challenged these boundaries to speculatively imagine futures, pasts, and presents when one critically interrogates these reified boundaries of Man and Nature that have been so emblematic of liberal modernity and its insidious development in Western capitalist/socialist fervor.

As she fundamentally uses theory to reframe her multisited ethnographies, political economic tracing, concepts of ecology, and even presentation of literary texts, Tsing provides us with a story of the matsutake mushroom and its proliferation of life even within, despite of, and totally un-synced from this notion of capitalist time, space, and exploitation. Drawing her framework from assemblage theory, Tsing then attempts to make us really think about the connections, happenings, that occur within a specific time and place--those pathways that have developed separately and converge and diverge based on its own happenstance and planned historical trajectories. In doing so, she fundamentally attempts to link and trouble these reified, inherited boundaries that we have between Man and Nature through a critical examination of the matsutake mushroom.

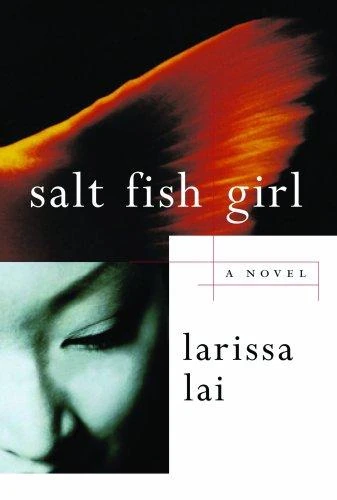

For this week's media précis, I return to a novel that I had read in the past that might be of interest to you all. It's Larissa Lai's Salt Fish Girl, published in 2002. Attached here is the preview that Amazon provides for its readers:

Salt Fish Girl is the mesmerizing tale of an

ageless female character who shifts shape and form through time and place. Told

in the beguiling voice of a narrator who is fish, snake, girl, and woman - all

of whom must struggle against adversity for survival - the novel is set

alternately in nineteenth-century China and in a futuristic Pacific Northwest.

Salt Fish Girl is the mesmerizing tale of an

ageless female character who shifts shape and form through time and place. Told

in the beguiling voice of a narrator who is fish, snake, girl, and woman - all

of whom must struggle against adversity for survival - the novel is set

alternately in nineteenth-century China and in a futuristic Pacific Northwest.

At turns whimsical and wry, Salt Fish Girl intertwines

the story of Nu Wa, the shape-shifter, and that of Miranda, a troubled young

girl living in the walled city of Serendipity circa 2044. Miranda is haunted by

traces of her mother’s glamourous cabaret career, the strange smell of durian

fruit that lingers about her, and odd tokens reminiscient of Nu Wa. Could

Miranda be infected by the Dreaming Disease that makes the past leak into the

present?

Framed by a playful sense of magical realism, Salt

Fish Girl reveals a futuristic Pacific Northwest where corporations

govern cities, factory workers are cybernetically engineered, middle-class

labour is a video game, and those who haven’t sold out to commerce and other

ills must fight the evil powers intent on controlling everything. Rich with

ancient Chinese mythology and cultural lore, this remarkable novel is about

gender, love, honour, intrigue, and fighting against oppression.

As literary texts are often interpreted and reinterpreted, I am interested to see how literary scholars might actually think about Larissa Lai's Salt Fish Girl in relation to Anna Tsing's theoretical framework for reading this book. The commonalities that I find here are actually ones that interrogate the role of olfaction, of smelling natural things in the face of capitalist ruins. As the matsutake mushroom exudes an aroma that is emblematic of autumn--built within different historical legacies of what matsutake mushroom mean for different groups of people globally, and historically based nonetheless--Larissa Lai's story also uses smell as a means of interweaving the possibility of life even in capitalist ruins. As the text itself oscillates between past and future present (e.g. 2044), the future based on Lai's narrative is fraught with overdeveloped areas of citizen life and severely underdeveloped, left-to-ruination, places outside of these cities where oddly enough durian fruit is grown, matures, and ripens. The smell of durian and salt-fish become particular ways that the antagonists and protagonists in the story find a sense of history and life lessons as the plot develops.

There is something here that I think the class would really enjoy if we were to take this kind of twinge to our studies of infrastructure. We've touched on the aspects of smell and our senses in how infrastructure is understood. For example, Fennell's book definitely shows us the role that affect around built environments become politically, culturally, and even economically salient as the residents' sense of heat become emblematic of their quotidian lives and what marks normalized life for them within the privatized housing projects. What I find particularly interesting and evocative about both Lai and Tsing's use of smell in their texts is the ways that natural life--albeit Tsing would probably shudder at this distinction between natural and unnatural life that I'm making here--can in fact breathe life and trouble the overdetermination on socio-technological development. The existence of the matsutake mushroom's smell, although used as means of contributing to capitalist relations, are also evocative of another life-world that has radical undertones for our study of infrastructure and capitalist relations: how does the extractive processes for capitalist profit still rely on these 'natural infrastructures' of smell and sense? There's a certain way then that we can reiterate the point that Tsing makes about the possibility of life in ruination--that indeed life reliant on the polyvocal, poly-rhythmic, multi-valenced, and collaborated happenings of the world can have emerging insurgencies that supersede and undermine the meta narratives capitalist relations evoke to justify their privatized extractive purposes.

Although I didn't provide a summary of her book here, I hope that you all would find some time to read Larissa Lai's novel. I find it phenomenal and actually compliments Tsing's text well.

Works Cited

Lai, Larissa. Salt Fish Girl: A Novel. Toronto: Thomas Allen, 2002. Print.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. New York: NYU, 2015. Print.

The Anthropocene

Tsing in her book shows how taking advantage of a wild mushroom can ruin the condition after the beginning of modern capitalism. The matsutake that grows below ground is impossible to cultivate, and hard to find, was the first living thing to emerge from the devastated landscape of Hiroshima. This mushroom high value makes it a great source of money for the post-war society with the job crisis. Tsing in her ethnographic study follows this spicy-smelling mushroom’s global commodity chain, from the forests of Oregon’s Cascade Mountains and elsewhere to Tokyo auction markets. She recounts her interviews with mushroom pickers, scientists, and entrepreneurs in the United States, Asia, and elsewhere to explore the matsutake’s commerce and ecology. The role of this species in the forests, how they impact the territory of animals related to if they like or dislike its spicy smell and how picking them to disturb their ecological surrounding. She writes about the problem of living despite economic and ecological ruination and how we need to think about a way for collaborative survival. Tsing shows how the matsutake, as an example, emblematic of survival amid changing circumstances, thrives in transformative collaboration with trees and other species and points the way toward coexisting with environmental disturbance.

For a long time astronomers have been telling us humanity is not the most important thing in the universe and evolutionary biologists established long ago that we're not even the greatest show on earth. Currently, geologists proposed that humanity is the most powerful force on the planet, shaping the environment. It looks we entered a phase of human domination or the anthropocene.

When human being took over the world?

Simon Lewis in the Nature article argues it started tens of thousands of years ago when people hunted large mammals to extinction. Others are as recent as the post-World War II period when such "persistent industrial chemicals" as plastics, cement, lead, and other fruits of the laboratory started to find their way into nature.

Humanity is changing the face of the earth with taking advantage of almost anything, from lands to mushroom. As Tsing states matsutake is one example to make us think about what we are doing to the world we are living in.

Gifting Mushrooms

Anna Tsing’s multi-sited ethnography of

the matsutake mushroom traces a commodity chain that provides Japan with these coveted

fungi. Forest animals such as elks and bears love the smell and bloody their

muzzles for the matsutake while certain slugs and insects avoid the smell. Slicing

with metal knives upsets the mushroom spirits. While reading I also thought of

the recent Oregon standoff and how Tsing complicates this narrative by

including the histories of the Kalamath as well as Lao, Mien, Hmong and Khmer

refugee-survivors who reinterpret their lives in Oregon foraging for mushrooms

as “freedom” in the context of lack of options for labor following Kalamath

land dispossession and decentralized assistance for refugees.

Tsing’s discussion of assemblages of

precarity made me rethink aspects of my parents’ resettlement experiences in

the U.S. My family arrived in the Carter years but resettled primarily during

the Reagan years which they recall as difficult. My parents come from rural

villages (Kien Svay and Takeo) but were able to complete high school in Cambodia

because of scholarships. Both had one week of English lessons at Khaodang, a

Thai refugee camp Tsing mentions in her book, prior to migrating to the US.

Because they were literate in Khmer and familiar with French schooling, both completed

technical degrees and found more secure employment unlike many of their friends

who were barely literate in Khmer. Nonetheless because I grew up around their

friends and their children who are like my cousins, we always received gifts of

food. Last month we received bags of dried shrimp their friends caught and

dried chili peppers. My parents also grow their food which used to embarrass me.

When I moved into on-campus family housing here at UCR, my mom rushed over to

plant a garden of lemongrass, chili peppers, mint, jack fruit, papaya, sugar cane and

green onions. I’ve since let some of it dry out. My dad pickles leafy greens

for me and delivers coconuts. Tsing’s book made me reimagine these everyday

occurrences embedded in small ecologies of communities across a continuum of

time. Tsing populates the Oregon landscape with an array of interconnected

stories despite and because of difference but also inflects my own experiences through

life as “coordination through disturbance” (163). Tsing’s description of the

Khmer woman who finds picking mushrooms a form of healing (89) made me think

about how my parents also find “freedom” in growing their own food. For this week,

I selected an eleven minute video about how some Cambodian seniors in Long Beach who garden and grow food.

Tsing’s descriptions of the autumn

matsutake also remind of the seasonal food and festivals in my town in Japan. People

gathered for imono or autumn

barbeques to grill an assortment of squash, small green pumpkins and mushrooms.

Winter for me was bowls of ramen noodles after weekends in the mountains. In

spring, some part-time retired coworkers picked sansai or mountain greens fry them lightly in tempura batter to

maintain the flavors. Cherry blossom season in full bloom in some parts of

Japan right now so for this week I included pictures of cherry blossoms in a

park near my old apartment.

The city lit up the park for these blossom

viewing parties and various friends hosted parties. My English club students

collected money to purchase chips, chocolate and drinks for our after school cherry

blossom parties. Graduations take place in the spring and teachers are shuffled

to new schools as the fiscal year for public schools begins and ends in spring.

The lamppost in the picture above reads “cherry blossom festival” with the sponsor’s

name written on the side “Kaisei Dining” a nearby restaurant. While life in

Japan was a bit too controlled for my tastes, the safety allowed activities like

attending a Friday evening office party, then check in to see who was

performing at a small hip hop club that felt like someone’s garage and finally

stroll home at 4 or 5am. This is a picture from one of those weekend morning walks

home in spring. After reading Tsing’s book, I decided to open my suitcase of kimonos and yukatas gifted from a friend’s mom and her

senior citizen group and the gifts still smell of my life in Japan. I'm not sure if the smells are imagined but they definitely bring back certain feelings and memories.

Tuesday, March 8, 2016

Tsing-dom Sits in Places: Pairing Anna Tsing and Keith Basso

REFERENCES:

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Basso, K. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places. University of New Mexico Press: New Mexico.

Is this the last blog of the quarter already?

Anna Tsing's latest act is most imaginative, daring, and timely. It speaks eloquently to the ‘mattering' ponderance of late across the disciplines, and of the assemblages and entanglements of infrastructure we have discussed in this seminar.

The structure of the book is ‘a riot of short chapters' because Tsing “wanted them to be like the flushes of mushrooms that come up after a rain: an over-the-top bounty; a temptation to explore; an always too many. The chapters build an open-ended assemblage, not a logical machine; they gesture to the so-much-more out there. They tangle with and interrupt each other — mimicking the patchiness of the world I am trying to describe”.

I wonder - given the ethnographies we have read and the unevenness between the chapters (such as in Roads or Undersea Network) - if Tsing is able to pull it through? In other word, did the intentional riotic organization of the book serve to fulfill the author's purpose?

This book reminds me much of the discussion in political ecology - particularly in regard to the departure from the separation between the human and the non-human worlds, and the work of capitalist investment and its ruins. Tsing dislodges the oppressive treatment of Nature by ‘Man’ and invoke the experiences of men, women, and people of color. She writes, “Without Man and Nature, all creatures can come back to life, and men and women can express themselves without the strictures of a parochially imagined rationality”.

In terms of capitalist readings, Tsing reminds us of the ‘arts of noticing,’ that we ought to “not just look ahead, but around.” As we look around, we will notice things that might have been left out of the discourses of ‘progress' and ‘modernization.’ The undersides of things. The non-dominant stuff in the view of world power structures, but the real things that help us understand our own world in new and necessary ways. To this end, she argues for a ‘third nature’:

Imagine "first nature" to mean ecological relations (including humans) and "second nature" to refer to capitalist transformations of the environment. This usage—not the same as more popular versions—-derives from William Cronon's Nature's Metropolis. My book then offers "third nature," that is, what manages to live despite capitalism. To even notice third nature, we must evade assumptions that the future is that singular direction ahead.

So I pair this daring read with Keith Basso's award-winning book Wisdom Sits in Places. Basso conducts fieldwork with the Apache people and recounts how four different groups view the significance of places in their culture. By looking at the Apache conceptions of their own culture and way of life, Basso shows a place has deep intimacy with the people that live on it and their experiences and vice versa, an intimacy that is much more fluid and interactive than the sacrosanct division between nature and society that Tsing calls out at the start of her book.

Why such pairing? One reason is because of the sense of placeness that Tsing communicates through the stories and images - the way she weaves fieldnotes with the ecology, capitalist processes, global undertakings, world making, and most of all - the mushrooming stuff. A second reason is because for me, Tsing's audacious text evokes a kind of neglected wisdom that can help us reorient our understanding of our own world: “the uncontrolled lives of mushrooms are a gift—and a guide—when the controlled world we thought we had fails". Third, the coupling of places and wisdoms seems to bring together both Tsing's offerings and place as a kind of infrastructure - the entanglement of human lives, the ecology, and the global markets.

And check out this beauty (an image, not even the mushroom itself), at just $450, complimentary shipping:

http://www.houzz.com/photos/44330679/Matsutake-Mushroom-Limited-Edition-Photograph-photographsIrregular Rhythms, Unintentional Design

What emerges in the ruins of industrialization? If human beings have

ruined the planet, caught in the drive to be modern, can we find a new way to

live? To what can we turn for a model? Tsing argues that, in order to survive, human beings must learn new ways of noticing, new ways of listening. She points out that, in spite of the

best-laid plans of states and capitalists, unpredictable occurrences surround

us. She writes,

Precarity is the condition of our time [...] Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable

encounters transform us; we are not in control, even of ourselves. Unable to

rely on a stable structure of community, we are thrown into shifting

assemblages, which remake us as well as our others. We can't rely on the status

quo; everything is in flux, including our ability to survive (20).

If we accept that, rather than the stable, planned, progressing civilization we narrate ourselves into, we live in

a state of precarity, we must reframe modern concepts of subjectivity and

individualism. “I” can never act independently or securely in a state of

precarity; “I” rely for survival upon other human and non-human organisms and

technologies (Tsing illustrates this idea with a walking stick). Tsing calls

this “assemblage,” “open-ended gatherings,” which sometimes become “happenings,”

encounters which are greater than the sum of their parts.

Tsing

illustrates assemblage and happenings by referencing polyphonic music,

particularly European Renaissance and Baroque polyphonic music. She writes,

These forms seem archaic and

strange to many modern listeners because they were superseded by music in which

a unified rhythm and melody holds the composition together. In the classical

music that displaced baroque, unity was the goal; this was ‘progress’ in just

the meaning I have been discussing: a unified coordination of time […] When I first

learned polyphony, it was a revelation in listening; I was forced to pick out

separate, simultaneous melodies to listen for the moments of harmony and

dissonance they created together. This kind of noticing is just what is needed

to appreciate the multiple temporal rhythms and trajectories of the assemblage (23-24).

Tsing titles

the first chapter, in which this paragraph exists, “Arts of Noticing.” In order

to understand how to survive in capitalist ruins, we must notice assemblage;

but assemblage, she implies, must be heard and felt. It is rhythms and

melodies. While modernity and progress relied upon eyes for their narratives, a sense which seems to privilege the linear, assemblage is heard (and, in the case of mushrooms, smelled). Noticing assemblage requires us to create and process knowledge in new ways.

These

ideas, in addition to the discussion later in the book of how John Cage

composed to reveal ambient sound, reminded me of the work of a colleague of

mine, No.e Parker. No.e studied Javanese and Balinese gamelan for several years

before returning to the United States to pursue a PhD in music composition.

Last summer and fall her work was on display at the UC Riverside Culver

Center’s Sweeney Art Gallery, where

she’d set up a container of compost filled with electrodes which connected to a

computer program and speakers, creating “a live soundscape of out of real-time

data.” The electrodes took temperature data, which was translated to hertz.

Citing Bennett’s Vibrant Matter, No.e writes of her composition project,

Composing

[De]Composition recontextualizes the biota of compost into an artistic material

and collaborator—joining the seemingly unconnected practices of home

composting, data collection, sound art and music composition into a

research-based, new media artwork. The project establishes compost— a complex,

living material—as an “actant … a source of action that … has sufficient

coherence to make a difference.”

The musical result of this project

had two parts. The first was the exhibit, which allowed listeners to hear

real-time compost temperature change as it occurred in the room. The second

component was a final performance, which took all the data and condensed it

into a wieldier composition, sped up and performed with MIDI sound. Both sound

files are available through links from her personal website, which you can

access here. I attended the final performance of the MIDI version (you can see

me lying on a yoga mat in one of the pictures on her website), and my

overwhelming sense at the end of the performance was wonder at what sound could

express. As Tsing likewise advocates, as we recognize the fault in monolithic

methods of modernity, we must offer instead “stories built through layered and

disparate practices of knowing and being” (159). Many composers bristled at

No.e’s project. Ignoring her complex conceptual and technical efforts, they questioned

how Composing [De]Composition could be a composition if she did not have

control over the notes. The pervasiveness of stories we tell ourselves about

the lone creative genius attempts to prevent deliberate “cross-species

coordinations” (156).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)